Erotics of art

Share

Images: Neenu Jacob, for LMSA. Taken at ‘Disco’ by Vivian Suter at Palais de Tokyo, Paris (2025).

We keep trying to decode art as if it’s a riddle with a solution. Susan Sontag, the American writer and cultural critic, argues something to this effect in her writing in ‘Against Interpretation’. She wanted us to stop untying knots and start feeling. Think of listening to a ghazal (or any kind of music you prefer): if a listener goes hunting for the “meaning,” they miss how the voice drags across a note, how the tabla presses at their chest, how the harmonium feels like it’s stretching time. Maybe that’s what she meant by an erotics of art- not explanation, but sensation. Which raises the question: if art can mean different things to different people, maybe its “objective” isn’t to tell but to touch?

It’s such a curious question - should art have an objective?

It’s the kind of question that brilliant people have circled around forever, but expert or not it’s always an exploration. A conversation. Perhaps it’s possible to just feel the way through it. Maybe the safest thing to admit is that there is no one answer. But that doesn’t stop one from wandering through a few ideas.

Think of Oscar Wilde - the flamboyant Irish writer, poet and playwright who called art “useless.” Not useless like trash, but useless the way a flower is useless - it doesn’t need a function to justify its being. A Van Gogh sunflower or a folk song hummed in the kitchen could just exist, unapologetically. There’s a kind of freedom in not asking art to do anything except be?

Tolstoy, who saw art as a kind of infection, thought it worked when the artist’s emotion passed into the audience, like a singer pouring heartbreak into a room, and everyone feeling the same ache in their chest. Like in concerts, where a whole crowd gasps or sways together. But what about when the artwork doesn’t want to hand us an emotion?

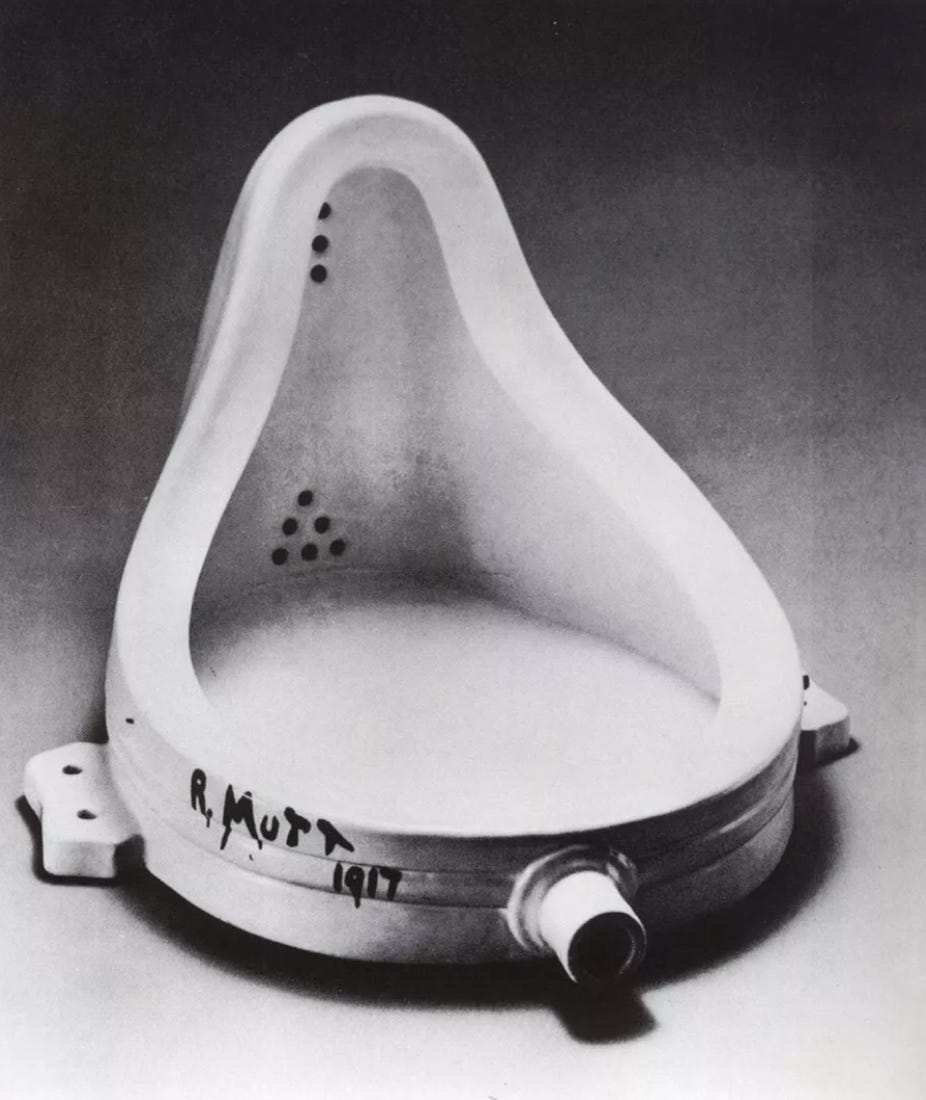

What about abstract paintings, or Duchamp’s urinal, where the “feeling” isn’t obvious? Is it still art if there’s nothing clear to catch?

Image: Marcel Duchamp’s Fountain, 1917, via Wikimedia Commons

Art may not be about transmitting emotion at all, but about making life feel fuller. Cooking a meal, arranging flowers, the way light falls on a wall - Dewey would have called these aesthetic experiences too. It makes art democratic, everywhere.

But then - if everything can be art, does the word start to dissolve? If our morning coffee is art and a Shakespeare play is also art, do they belong to the same category? Or do we need boundaries to protect the word?

Arthur Danto said art needs a frame - not just a wooden one, but a cultural one. Duchamp’s urinal in a bathroom is plumbing; in a gallery it’s a provocation(?!). Even an everyday thing can become art if placed in a certain context. But it raises a tricky question: does art only exist because influential institutions say so? Where does that leave paintings in village temples, or the crochet a grandmother makes, things born outside galleries?

Which brings us to the fact that art isn’t about personal feelings at all, but about creating a shared savor of emotion. Like when a Kathakali performance leaves the audience steeped in karuṇa (pathos) or adbhuta (wonder), no matter what the performer themselves is feeling that day. It isn’t empathy; it’s something more distilled, something we can all taste together. That is a beautiful image: art not as a message or sensation alone, but as a flavor carried in our mouths after the performance ends.

So where does that leave us? Somewhere in this wandering-between art as useless as a sunflower, art as sensation, an infection, the shimmer of everyday life. Or art as the frame around a urinal. Maybe art doesn’t need one objective. Maybe it needs a family of them. Or maybe it needs none at all. Hard to tell. Which makes it easy to keep gravitating towards these questions.

For now, visualise it as a spectrum.

-

Draw a tiny line: left end = no objective at all, right end = strong objective.

-

Place today’s piece on the line by gut feel.

-

Nudge it two steps left, then two steps right (just in imagination) and ask: what opens up / what closes down with each move?

-

Stop where you feel the most generous attention - maybe that’s the answer for today.