Why We Keep Coming Back to Art

Share

Art, always more than what meets the eye, is about memory, connection, protest, storied tellings and the way it reminds us what it means to be alive.

In a world designed to move fast - where everything is scrollable, skippable, sped up -art gives us a reason to pause. Again and again, we come back. To galleries. To paintings from decades ago. To sculptures, installations, zines, textile works, photographs - some of which we don’t fully “get.” But they stay with us. Why? It’s tempting to say it’s just about aesthetics. But the more you look at art, the more you realise: it’s not all skill and technique, it’s the voice, it’s the about, it’s the grammar, it’s the telling. Art is witness. It holds memories. It asks questions. Sometimes it screams. Other times it just sits quietly in the room with you and your feelings. And in that way, it becomes something we return to - not just to look, but to feel seen.

Take Amrita Sher-Gil.

Image: Three Girls (1935), National Gallery of Modern Art

Three Girls (1935), perhaps her most renowned painting, portrays three rural Indian women seated with downcast eyes. The muted reds and browns encapsulate the weight of their interiority, their emotional exhaustion, and their unspoken thoughts. As Malcolm Fernandes observes, the painting’s composition and color palette evoke “the echoes of the deep-rooted ideas of subservience of women prevalent in the subcontinent then, and even today” .

In an era when women were often relegated to the roles of muses or background figures, Sher-Gil’s decision to depict them as subjects with agency was considered radical at the time.

Born in Budapest in 1913 to a Punjabi Sikh father and a Hungarian-Jewish mother, Sher-Gil’s life and work navigated the intersections of continents, cultures, and inner contradictions. At 19, she painted Young Girls (1932), a piece that secured her admission to the École des Beaux-Arts in Paris. While technically accomplished, it wasn’t until her return to India that her art acquired the profound depth she’s celebrated for today.

Sher-Gil’s approach was feminist, though not in the overtly political sense. It was intimate and personal, capturing the nuanced experiences of Indian women. Her paintings invite viewers to witness the silent strength and resilience of her subjects, making them enduringly relevant.

We continue to return to Sher-Gil’s work not merely for its aesthetic appeal but because it offers a profound commentary on the human condition. Her art serves as a testament to the complexities of identity, gender, and cultural hybridity, reminding us of the power of visual narratives to convey what words often cannot.

But Sher-Gil wasn’t alone.

Art isn’t only about pain, protest, or memory. It’s also about joy. About comfort. About absurdity, humour, play. The Mexican poet Cesar Cruz once said, “Art should comfort the disturbed and disturb the comfortable.” And sometimes, it does both at once.

Take Japanese artist Yayoi Kusama.

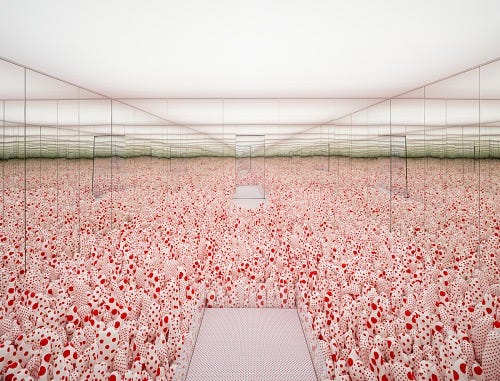

Known for her immersive Infinity Mirror Rooms, whimsical polka dots, and explosive use of color, Kusama’s work is often described as joyful, even childlike. But it’s joy with depth. Her installations invite us into fantastical, repetitive, infinite spaces - like walking into someone’s dream. You don’t just see the art. You’re inside it.

Image: Infinity Mirror Room – Phalli’s Field (1965), Hirshhorn Museum

What makes her work so memorable isn’t just its spectacle - it’s the feeling of losing and finding yourself at the same time. People wait hours just to spend 30 seconds in a room covered in dots and mirrors. Why? Because in a world that often feels overwhelming or isolating, Kusama’s art offers a moment of escape. A portal into wonder. A strange comfort.

And we need that, too.

Art doesn’t have to scream to make a point. It doesn’t even have to make a point. Sometimes it just holds you quietly, reminds you that you’re alive, that beauty and imagination still exist - even in chaos. Kusama, who has lived most of her life voluntarily in a psychiatric hospital, once said: “With just one polka dot, nothing can be achieved. In the universe, there is the sun, the moon, the earth, and hundreds of millions of stars.” Her dots are part of a bigger constellation - just like we are.

Fast forward to now.

Indian contemporary art has exploded into new forms - video, performance, digital installations and new voices. Especially women, queer, Dalit, and Adivasi artists who’ve been historically pushed to the sidelines.

So, why do we keep coming back?

Because art remembers what & when people forget. It asks us to sit with discomfort. To feel things we don’t always have the words for. And it doesn’t offer easy closure, which is maybe why it feels more truthful than most news, ads, or Instagram posts.

Image: Sunflower Seeds (2010), Take Museum

Consider Ai Weiwei, the Chinese contemporary artist and activist. His installation Sunflower Seeds (2010) featured 100 million hand-painted porcelain seeds, symbolizing mass production and the loss of individuality in contemporary society.

Through his art, Ai Weiwei critiques societal issues and advocates for human rights, reminding us that art can be a powerful tool for social commentary and change.

So whether it’s Amrita Sher-Gil painting the sadness of three women in 1935, or Ai Weiwei casting millions of porcelain seeds across a gallery floor in 2010, the reason we keep coming back is the same: art makes space for what’s too big, too strange, or too sacred to put into words. It helps us feel when everything else tells us to think faster.

And isn’t that something we should hold on to?